My last post was about faith. I'm no closer to having faith, but I'm more comfortable with the idea.

I think that normal people simply see the world in a much more subjective emotional way than I do. They believe in things because it feels right. And that's all there is to it.

That's not a bad thing. John Maynard Keynes wrote about how most business ventures are negative expected value from the get-go, and it requires an irrational belief in the prospects of success (that he called animal spirits) for anything to get started in the first place.

On to utility value. It's a term that basically means how good you think something is. For example a piece of cake has a utility value that's different for everyone, depending on how much you like cake. There's no hard and fast method for determining utility value, but often you can make statements about when something has a higher utility value than something else; for example, we'd all like $200 more than $100.

I've been noticing of late that when people go after stuff, the way they pick what they want involves not only how good the thing is for them, but also the emotional high or low that comes along with getting it. For instance, I really like to save money. I recently saved $5/month on car insurance by increasing our deductible. That's a good thing to do, but it's not great. It's just $5 and isn't going to make me that much happier. I'm happy out of proportion of the true utility value of $5/month (which probably amounts to something extra at the grocery store that I won't really notice). And the same is true for me and others, in lots of different areas in which we judge value: there's this "emotional overlay" on the perceived utility value of stuff that makes us go after stuff that might not be sensible or worth the effort.

I've been applying this by trying to be less anal about stuff. I get happier than I should about keeping my behaviour in a box (bed time, exercise, etc...), so I figure I can optimize my life further by ignoring the urge to panic at 9:50pm when we're not in bed yet.

P.S. Another example of emotional overlay on something that's good but not that good. I'm reading a chess book now that has 607 different examples, divided into various sections. I want to work through this book on a best-effort basis... I want to be able to go through 50 positions and stop. So I wrote a script that randomized the numbers 1 though 607 so I can go in "order" and hop around the book and sample the various sections more or less equally. I seem to have an irrational desire to be in a box.

Wednesday, September 9, 2009

Friday, April 10, 2009

Blogworld, I have a question

I've been reading this book. It's a bunch of short essays about people's personal philosophies and guiding principles.

Unsurprisingly, lots of people talk about faith. Faith in God, faith in humanity, faith in their prospects for success, faith in themselves.

I have a funny thing to tell you about myself. When I tell you, you're going to look at me like a small child who is trying to figure something out. I know this because three different people have given me this look when I explain this to them.

I don't understand faith. I don't have faith in things. To me, faith is a very surprising and foreign concept. It baffles me that faith is something people do.

I want to explain this carefully in order to be understood. When I say I believe something, I mean precisely the following: I have a picture in my head of a pie chart describing all the possible outcomes or explanations for the situation in question. The size of each slice of the pie represents how likely I think it is, as determined by all the information I have. If one of the slices takes up almost the entire pie, then I believe it.

However, faith appears to be a whole different ballgame. From what I understand of faith, the idea is to believe something with certainty, without checking what the actual probability of it is. Or, believing something in spite of what the probability actually is.

The example that came up recently was this: What if The Superhero came down with a terminal illness, and the doctors said that people in her condition died 80% of the time and were cured 20% of the time. Would I have faith that she would be one of the 20% who lived?

I said of course that in that situation I think she has an 80% chance of dying, and a 20% chance of living. The reason is that the doctors' opinions are the best information that I have available. In the absence further evidence, my working theory about this illness would be that The Superhero would most likely die.

The reaction I got was this funny smile that you'd give a child who doesn't understand something very simple.

Since I've been investigating the nature of faith, I've had a few similar conversations. It always leaves me with the creepy feeling of being in a madhouse, like I'm the only sane person left and everyone else has taken temporary leave of their senses.

Let me try to explain how I feel about this with an analogy. A group of intelligent people who's opinion you typically respect are standing around playing with an ordinary 6-sided die. You've been rolling it for a while, and you've gotten each of the numbers 1 through 6 with similar frequency. Then people start talking about what the probability is that the next roll is going to be a 6. You say calmly that the probability of a 6 is about 1 in 6. Everyone looks at you like you've made a very simple and fundamental error in judgment, and they proceed to explain to you that the probability of rolling a 6 on the next roll is nearly 100%. You look at them suspiciously and ask if there's some trick, like they've stuck a magnet or a weight in the die or something to influence the outcome. They maintain the same patronizing smile as they explain that not only have they not messed with the die in some way, but they arrived at the conclusion that the next roll would almost certainly be a 6 specifically by not analyzing how a die works and what is in fact most likely to happen.

This is how I feel. I feel as though some kind of mind control has taken over people who otherwise appear to be sensible most of the time.

So Blogworld, please enlighten me! What is this faith business?

Unsurprisingly, lots of people talk about faith. Faith in God, faith in humanity, faith in their prospects for success, faith in themselves.

I have a funny thing to tell you about myself. When I tell you, you're going to look at me like a small child who is trying to figure something out. I know this because three different people have given me this look when I explain this to them.

I don't understand faith. I don't have faith in things. To me, faith is a very surprising and foreign concept. It baffles me that faith is something people do.

I want to explain this carefully in order to be understood. When I say I believe something, I mean precisely the following: I have a picture in my head of a pie chart describing all the possible outcomes or explanations for the situation in question. The size of each slice of the pie represents how likely I think it is, as determined by all the information I have. If one of the slices takes up almost the entire pie, then I believe it.

However, faith appears to be a whole different ballgame. From what I understand of faith, the idea is to believe something with certainty, without checking what the actual probability of it is. Or, believing something in spite of what the probability actually is.

The example that came up recently was this: What if The Superhero came down with a terminal illness, and the doctors said that people in her condition died 80% of the time and were cured 20% of the time. Would I have faith that she would be one of the 20% who lived?

I said of course that in that situation I think she has an 80% chance of dying, and a 20% chance of living. The reason is that the doctors' opinions are the best information that I have available. In the absence further evidence, my working theory about this illness would be that The Superhero would most likely die.

The reaction I got was this funny smile that you'd give a child who doesn't understand something very simple.

Since I've been investigating the nature of faith, I've had a few similar conversations. It always leaves me with the creepy feeling of being in a madhouse, like I'm the only sane person left and everyone else has taken temporary leave of their senses.

Let me try to explain how I feel about this with an analogy. A group of intelligent people who's opinion you typically respect are standing around playing with an ordinary 6-sided die. You've been rolling it for a while, and you've gotten each of the numbers 1 through 6 with similar frequency. Then people start talking about what the probability is that the next roll is going to be a 6. You say calmly that the probability of a 6 is about 1 in 6. Everyone looks at you like you've made a very simple and fundamental error in judgment, and they proceed to explain to you that the probability of rolling a 6 on the next roll is nearly 100%. You look at them suspiciously and ask if there's some trick, like they've stuck a magnet or a weight in the die or something to influence the outcome. They maintain the same patronizing smile as they explain that not only have they not messed with the die in some way, but they arrived at the conclusion that the next roll would almost certainly be a 6 specifically by not analyzing how a die works and what is in fact most likely to happen.

This is how I feel. I feel as though some kind of mind control has taken over people who otherwise appear to be sensible most of the time.

So Blogworld, please enlighten me! What is this faith business?

Sunday, April 5, 2009

Learning Things I Already Know

In my old age and wisdom, I've come to realize the following:

a) It's better to give than to receive.

b) Raising kids the most challenging and rewarding thing I'll ever do.

c) Lessons mean more when you learn them for yourself.

d) Money is not the most important thing in life.

What I want to talk about today is not these things themselves, but the true nature of this class of knowledge.

These things are examples of what I'd call "canned" statements. You don't have to wait very long in polite company before hearing one of these statements. Making one of these comments confers great honour and nobility upon the speaker.

The tricky thing about these statements is that they're well known and socially acceptable, and they also happen to be true. Furthermore, they would be non-obvious if they weren't cliches: this class of knowledge is the kind of thing that you have to pay to find out. It takes hard work and maturity to understand these things fundamentally.

When someone says something non-obvious and true, it's clear that they must have thought it through. If someone points out that an object near the earth's surface falls approximately 4.9m in the first second, they've either measured it themselves or integrated 9.8 twice from 0 to 1. But with cliche's you can't tell if you're just listening to a parrot or if someone has actually had a fundamental realization about life.

On the upside, though, whenever I do happen to learn one of these things "for real", I get this funny little "aha" moment when I realize that the thing I just learnt maps onto one of those well-known statements. It's something like "Oh, you dopey Mr. Superhero, you're heard that about 50,000 times and you only understand it NOW???".

a) It's better to give than to receive.

b) Raising kids the most challenging and rewarding thing I'll ever do.

c) Lessons mean more when you learn them for yourself.

d) Money is not the most important thing in life.

What I want to talk about today is not these things themselves, but the true nature of this class of knowledge.

These things are examples of what I'd call "canned" statements. You don't have to wait very long in polite company before hearing one of these statements. Making one of these comments confers great honour and nobility upon the speaker.

The tricky thing about these statements is that they're well known and socially acceptable, and they also happen to be true. Furthermore, they would be non-obvious if they weren't cliches: this class of knowledge is the kind of thing that you have to pay to find out. It takes hard work and maturity to understand these things fundamentally.

When someone says something non-obvious and true, it's clear that they must have thought it through. If someone points out that an object near the earth's surface falls approximately 4.9m in the first second, they've either measured it themselves or integrated 9.8 twice from 0 to 1. But with cliche's you can't tell if you're just listening to a parrot or if someone has actually had a fundamental realization about life.

On the upside, though, whenever I do happen to learn one of these things "for real", I get this funny little "aha" moment when I realize that the thing I just learnt maps onto one of those well-known statements. It's something like "Oh, you dopey Mr. Superhero, you're heard that about 50,000 times and you only understand it NOW???".

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Relativity and Marriage

This is an Emergency Post! I've already posted today, but I just had a conversation with The Superhero that MUST be recorded.

The Superhero is rearranging the living room furniture...

The Superhero: "Do you think the couch will fit between the cabinet and the wall?"

Me: "No way, it's too long."

The Superhero: "Sure it will..." pushes the couch into the spot with room to spare "Ha, there!"

Me: "Well surely that's because it's moving close to the speed of light and it's length is contracted."

The Superhero: "Well if the couch is moving, then we are also moving [since we don't observe it moving] so there would be no length contraction!"

Ha! So, Future Self, as you get older and your body gives out and your mind starts to fade, and you wonder whether it was all worthwhile whether your life was well-spent, remember this: You once had it all. You had a hot 27-year old wife who cooks you pizza, is dirty in bed, and sasses you with Einstein.

You can die a happy man.

The Superhero is rearranging the living room furniture...

The Superhero: "Do you think the couch will fit between the cabinet and the wall?"

Me: "No way, it's too long."

The Superhero: "Sure it will..." pushes the couch into the spot with room to spare "Ha, there!"

Me: "Well surely that's because it's moving close to the speed of light and it's length is contracted."

The Superhero: "Well if the couch is moving, then we are also moving [since we don't observe it moving] so there would be no length contraction!"

Ha! So, Future Self, as you get older and your body gives out and your mind starts to fade, and you wonder whether it was all worthwhile whether your life was well-spent, remember this: You once had it all. You had a hot 27-year old wife who cooks you pizza, is dirty in bed, and sasses you with Einstein.

You can die a happy man.

My Clothes are Getting Lazy

Dear Clothes,

What is going on these days, Clothes? I think you've changed.

I remember a time, not so long ago, when you would cheerfully hop out of the hamper, trot downstairs and tumble into the washer. The jeans would jump in with some detergent, the dress shirts would adjust the dial, and the sweaters would close the lid.

You were such a great team, Clothes. The underwear would keep an eye on the socks so they wouldn't escape from the dryer, and the T-shirts would comfort the pajama pants during the spin cycle. You had a buddy system for the trip from the washer to the dryer, and you all had such a great time tumbling around together.

Then you'd parade back upstairs, marching in proud, clean lines, to find your homes again on hangers and in drawers.

I never actually saw this process, but I assume that's how it must have happened. The stained, wrinkled heap of old clothes magically reappeared nicely folded and hanging ready to serve again.

But Clothes, you have changed. You are despondent and depressed, laying around in the hamper for days. You ignore your dirt, your creases, your odors, and do nothing about it. Is it something I said? Something I did? Have I not paid enough attention to you, Clothes?

Now I must haul you down to the washer myself, move you from washer to dryer to basket to drawer without any help from you, Clothes. What has happened to you, Clothes?

Sincerely,

Mr. Superhero

P.S. Clothes, it doesn't have anything to do with this, does it?

What is going on these days, Clothes? I think you've changed.

I remember a time, not so long ago, when you would cheerfully hop out of the hamper, trot downstairs and tumble into the washer. The jeans would jump in with some detergent, the dress shirts would adjust the dial, and the sweaters would close the lid.

You were such a great team, Clothes. The underwear would keep an eye on the socks so they wouldn't escape from the dryer, and the T-shirts would comfort the pajama pants during the spin cycle. You had a buddy system for the trip from the washer to the dryer, and you all had such a great time tumbling around together.

Then you'd parade back upstairs, marching in proud, clean lines, to find your homes again on hangers and in drawers.

I never actually saw this process, but I assume that's how it must have happened. The stained, wrinkled heap of old clothes magically reappeared nicely folded and hanging ready to serve again.

But Clothes, you have changed. You are despondent and depressed, laying around in the hamper for days. You ignore your dirt, your creases, your odors, and do nothing about it. Is it something I said? Something I did? Have I not paid enough attention to you, Clothes?

Now I must haul you down to the washer myself, move you from washer to dryer to basket to drawer without any help from you, Clothes. What has happened to you, Clothes?

Sincerely,

Mr. Superhero

P.S. Clothes, it doesn't have anything to do with this, does it?

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

This and That

One of my goals in starting a blog was to capture the state of my life at various points so they don't drift off into the foggy blur of old memories. So today I'm going to write about a bunch of random stuff that's going on right now.

- The monkeys are at a great age right now (1.5/3/4/4). The Superhero set up the basement a couple of weekends ago for to be kid-friendly, and they're actually using it independently some of the time. About a year and a half ago I remember the transition when we went from having to do basic housework when everyone was sleeping to being able to do some of it when the kids were awake. Now we're transitioning to being able to do grown-up things while the kids are awake. It's great. Last Saturday we had sex twice in the morning while the kids played on the main floor.

- On that note, The Superhero has been very amourous lately; sans any kind of reading material that might influence her in that direction. I thank hormones, helped along by the recent egg donation.

- The kids getting old enough to just about understand some things. They know that I go to work to make money, and we use it to buy food. I tried to explain taxes the other day, but it didn't go over so well.

- I'm on a physics kick recently. I just worked out the speed of a small "wobble" in a disk as compared to the speed of rotation of the disk. Turns out the disk wobbles at twice the speed of the disk's rotation for small wobbles. It follows from setting up the equations for the position of any particle at any time, differentiating to get speed and acceleration, and then requiring that the angular momentum is constant since there's no outside torques. I'm now reading the popular version of the theory of relativity by Einstein. I tried the real version (with all the math details) and it became so dense that I switched to the softer one, sadly. It's the neatest physics problem there will probably ever be, since:

- It's very simple: consider that non-accelerating frames of reference are indistinguishable, and that the speed of light is constant. The whole problem is: if these two things are true, what are the implications? (the apparent paradox is that if you walk away from me and I shine a flashlight at the speed of light, you'd think that you'd observe the light going at the speed of light less the speed of you're walking, but we said the speed of light is constant and each frame of reference is equivalent for judging that, so you actually also see the light going at the speed of light!)

- The subject is things that are more or less part of our everyday experience (trains, embankments, etc.). It's not like particle physics where the trick is imagining what tiny things we've never see are like.

- The whole trick is questioning the simplest things we depend on (like our conceptions of space and time), and remembering what you can still think and what is wrong. Very tricky!

Monday, March 2, 2009

The Nature and Limits of Scientific Investigation

I've spent most of my spare time since my last post thinking about Problem #3, and trying, mostly unsuccessfully, to torture The Superhero with it as well. I'm happy to report that I now understand the jump between the fuzzy fog inside my head and the math laws that describe reality.

Today I'm going to explain the nature of how we understand our world and what limitations are in how we can describe it. I'm also going to try to explain this in a lay-person-accessible way; I like the challenge of explaining complicated things in ways that make sense to people not acquainted with the details of the problem, and it's a good test for how well I understand things.

First, let's recap the problem. Suppose you and I are trying to measure the length of a piece of string. We'd hold the string up against a yardstick and argue back and forth about how long it is. I think it's 19.4 inches, and you think it's 19.6 inches. We decide in order to break the tie we're going to get a yardstick with ticks every 1/4 of an inch, and measure again. It turns out it's a bit on the long side of 19.5 inches, so you're closer to the right answer. But suppose I'm difficult and insist that it's not 19.6 inches: I say it's 19.58 inches. You can see this could go on for a while, getting ever-more precise yardsticks and eventually requiring magnifying glasses and microscopes to tell who's right. Still we could go on and on forever, never agreeing on the exact length, until we get down to the molecular level and we'd start arguing where the "end" of the string is in on the frayed end of the string.

To state the problem succinctly, our perceptions are foggy, and subject to interpretation. When we observe something, you and I will not necessarily agree on the measurement. So how do we make laws about the world? When we say a toothbrush falls at a constant acceleration of 9.8m/s2, what do we mean exactly, and how can we measure it in a way we can agree on?

So thinking about this, I the first thing I did was study myself looking at stuff, observing what the problems were that stop me from understanding what I'm seeing in a well-defined way that I can make rules about. I noticed 3 things:

Unreliability can be gotten around as well. The unreliability in my perceptions can be gotten around by using measurement devices that start out in exactly the same state. I could build a reliable thermometer that will always report the same temperature in the same way.

The core problem with us agreeing on the how long the string is, is the fact that our perceptions come to us in a way that's not formally defined. We can never decide exactly where the end of the string is; we think it's about 19.5 inches, but we can't decide because we both have this estimation that's going on inside our heads that comes out slightly differently.

The key to understanding how this works clearly, is that our brains are also part of the physical world, and in this case are forming part of the experiment. On close examination, it's clear that I am making a direct and exact measurement of the physical world, but the measurement is not just a function of the string. It's a function of everything. It's a function of the psychological estimation procedure in which I guess the end of the string is about 4/10 of the way between the 19 inch line and the 20 inch line. It's also a function of how the gravitational attraction from between the string and my brain stretches the string toward my head. It's also a function of the tides of the Pacific Ocean and how that water is pulling the string. The measurement device, and everything else in the universe, contributes towards getting the number 19.4. However, 19.4 is completely function of the real world, not a concoction of some mystical "consciousness" that's actually just a configuration of atoms in my brain.

If you don't want to measure anything about your psychology, you can pass your brain information from the outside world in a way that doesn't need interpretation. That is, you can make a measurement device that has a little display that shows you numbers, or little blinking lights that lend themselves to a non-fuzzy interpretation. So if your thermometer says 8 degrees, you and I can look at that and agree exactly what it says. The measurement is still a function of not only the ambient temperature but also of the thermometer (for instance, how it rounds the temperature off to 8 degrees). It's also technically a function of your brain, since maybe the thermometer says 18 degrees and you just missed the 1. But assuming we can read the device without error, we'll all agree on what it says.

So far so good. Despite the 3 weaknesses of how information comes into my brain when I hold a banana and look at it, these can be overcome and I can get direct, well-defined measurements of the physical world that I can then get to work on making rules about. I can put out my digital thermometer, take periodic readings, and try to notice patterns in how the temperatures change with the seasons and make scientific discoveries. Furthermore, I can create any kind of coccamamy ideas in my head to explain it, and they're all equally good, provided that they predict my observations correctly.

However this does not totally answer the questions of how we can conduct science. Suppose I come up with some law that describes how the temperature changes with the seasons. This is only a description of what my thermometer read at various times and rules about how the readings relate to each other. When someone else tries to interpret that and reproduce my results, he'll come up with some experimental setup that looks kind of like mine, but isn't quite the same. And we'll be back in the same position we were in trying to measure the string; I can't describe exactly how to reproduce the conditions of my experiment so that the readings off the next guy's digital thermometer measure the exact same thing as mine did.

So in conclusion, we can say the following about the physical laws (rules) we make up to describe our world:

P.S. Through this train of thought I've come up with a much more important question. How on earth do we manage to have such success in the world by making judgements on perceptions that can't be tested for whether they follow rules? Unfortunately, this is a question for psychology and neuroscience to answer. You can't figure it out just by thinking.

Today I'm going to explain the nature of how we understand our world and what limitations are in how we can describe it. I'm also going to try to explain this in a lay-person-accessible way; I like the challenge of explaining complicated things in ways that make sense to people not acquainted with the details of the problem, and it's a good test for how well I understand things.

First, let's recap the problem. Suppose you and I are trying to measure the length of a piece of string. We'd hold the string up against a yardstick and argue back and forth about how long it is. I think it's 19.4 inches, and you think it's 19.6 inches. We decide in order to break the tie we're going to get a yardstick with ticks every 1/4 of an inch, and measure again. It turns out it's a bit on the long side of 19.5 inches, so you're closer to the right answer. But suppose I'm difficult and insist that it's not 19.6 inches: I say it's 19.58 inches. You can see this could go on for a while, getting ever-more precise yardsticks and eventually requiring magnifying glasses and microscopes to tell who's right. Still we could go on and on forever, never agreeing on the exact length, until we get down to the molecular level and we'd start arguing where the "end" of the string is in on the frayed end of the string.

To state the problem succinctly, our perceptions are foggy, and subject to interpretation. When we observe something, you and I will not necessarily agree on the measurement. So how do we make laws about the world? When we say a toothbrush falls at a constant acceleration of 9.8m/s2, what do we mean exactly, and how can we measure it in a way we can agree on?

So thinking about this, I the first thing I did was study myself looking at stuff, observing what the problems were that stop me from understanding what I'm seeing in a well-defined way that I can make rules about. I noticed 3 things:

- My perceptions are incomplete. I see some things and not others. For instance, I don't see x-rays.

- My perceptions are unreliable. That is, I perceive the same thing in two different ways if it happens to me twice. For instance, when I wake up, things are much brighter than when I come in from out in the sun

- My perceptions are undefined. This means that the lower levels of my brain that take the stimulation from my eyeball and turn it into a meaningful picture for me present it to my higher-level consciousness don't present that picture in a way I can write down and communicate clearly. For instance, when I look at two pieces of art and one looks nice and one does not, I can't describe to you every detail of why I think that's so.

Unreliability can be gotten around as well. The unreliability in my perceptions can be gotten around by using measurement devices that start out in exactly the same state. I could build a reliable thermometer that will always report the same temperature in the same way.

The core problem with us agreeing on the how long the string is, is the fact that our perceptions come to us in a way that's not formally defined. We can never decide exactly where the end of the string is; we think it's about 19.5 inches, but we can't decide because we both have this estimation that's going on inside our heads that comes out slightly differently.

The key to understanding how this works clearly, is that our brains are also part of the physical world, and in this case are forming part of the experiment. On close examination, it's clear that I am making a direct and exact measurement of the physical world, but the measurement is not just a function of the string. It's a function of everything. It's a function of the psychological estimation procedure in which I guess the end of the string is about 4/10 of the way between the 19 inch line and the 20 inch line. It's also a function of how the gravitational attraction from between the string and my brain stretches the string toward my head. It's also a function of the tides of the Pacific Ocean and how that water is pulling the string. The measurement device, and everything else in the universe, contributes towards getting the number 19.4. However, 19.4 is completely function of the real world, not a concoction of some mystical "consciousness" that's actually just a configuration of atoms in my brain.

If you don't want to measure anything about your psychology, you can pass your brain information from the outside world in a way that doesn't need interpretation. That is, you can make a measurement device that has a little display that shows you numbers, or little blinking lights that lend themselves to a non-fuzzy interpretation. So if your thermometer says 8 degrees, you and I can look at that and agree exactly what it says. The measurement is still a function of not only the ambient temperature but also of the thermometer (for instance, how it rounds the temperature off to 8 degrees). It's also technically a function of your brain, since maybe the thermometer says 18 degrees and you just missed the 1. But assuming we can read the device without error, we'll all agree on what it says.

So far so good. Despite the 3 weaknesses of how information comes into my brain when I hold a banana and look at it, these can be overcome and I can get direct, well-defined measurements of the physical world that I can then get to work on making rules about. I can put out my digital thermometer, take periodic readings, and try to notice patterns in how the temperatures change with the seasons and make scientific discoveries. Furthermore, I can create any kind of coccamamy ideas in my head to explain it, and they're all equally good, provided that they predict my observations correctly.

However this does not totally answer the questions of how we can conduct science. Suppose I come up with some law that describes how the temperature changes with the seasons. This is only a description of what my thermometer read at various times and rules about how the readings relate to each other. When someone else tries to interpret that and reproduce my results, he'll come up with some experimental setup that looks kind of like mine, but isn't quite the same. And we'll be back in the same position we were in trying to measure the string; I can't describe exactly how to reproduce the conditions of my experiment so that the readings off the next guy's digital thermometer measure the exact same thing as mine did.

So in conclusion, we can say the following about the physical laws (rules) we make up to describe our world:

- All observations we make that somehow get translated into a well-defined thought are exact physical measurements about our world, including our brain. By constructing our measurements in clever ways, we can limit the impact that our brain and other irrelevant effects have on measuring, but results will always be a function of everything.

- The theories we invent to explain the world, exist solely within our brains. We might make predictions based on a theory of electrons, and an alien race might make identical predictions with no concept of electrons, and we can both be equally right. The only test of the theory is does it predict measurements properly.

- The interpretation of how to make the measurement to test against the theory is fundamentally dependent on human interpretation. There is no way to describe a theory in which two people will make measurements to test it in precisely the same way and never disagree. By describing measurement techniques you can get people to agree more often and measure in more similar ways; but you will never get them to agree 100% of the time.

P.S. Through this train of thought I've come up with a much more important question. How on earth do we manage to have such success in the world by making judgements on perceptions that can't be tested for whether they follow rules? Unfortunately, this is a question for psychology and neuroscience to answer. You can't figure it out just by thinking.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

The Shaky Foundations of Science: The Theory of Falling Toothbrushes

I've been reading Classic Feynman, which has gotten me thinking about physics again, and science in general.

There are some problems you encounter when you try to figure how stuff works in the real world. Some of them are very clear to me; they're problems, but I understand them. There are other problems that aren't very clear to me, and hang around in the back of my mind like little nagging doubts. Let me explain.

This morning I was brushing my teeth and imagined that I knew nothing about physics and was trying to figure out what happens when you drop a toothbrush. That's all science is after all: you see stuff happen and try to understand it better and explain it.

So what would I do?

I'd start dropping the toothbrush and watching it. I'd watch it again and again. Soon I'd probably notice that it starts out slow and speeds up as it falls. Maybe I'd get a video camera and videotape the toothbrush falling and watch the tape frame by frame, and figure out exactly how fast it's falling. I'd notice that it falls at almost the exact same way every time. Sooner or later I'd come up with the Theory of Falling Toothbrushes, which might be stated as follows:

Toothbrushes fall at a constant acceleration: 9.8m/s2

So, is this a good theory? It has some things in it's favour, principally that it predicts the position of the falling toothbrush at a given time to within the error tolerance of most experimental setups you might imagine.

This theory is as good as a scientific theory can be. It has some problems, but, as far as I can tell, these problems are fundamental to scientific theories; that is, these problems exist for every scientific theory that could be invented.

Here are the problems I can see with this:

Category 1: Problems I Understand

These problems are not particularly interesting. They're just occupational annoyances that scientists face. I'll explain them here to distinguish them from the interesting questions.

Problem #1: Almost every physical process you can observe is very very complicated. For instance, when you drop a toothbrush, it bangs into air molecules, and starts out with a small bit of angular momentum since you can't drop it straight down. These will make your experiment come out a bit different every time, and the the complications they introduce will be incalculable. This is not news: The Theory of Falling Toothbrushes actually describes what would happen if you dropped a toothbrush from a perfect dropping machine that imparts no "twist" or "push" as it drops, in a perfect vacuum. If this was the only objection to the theory, it would still describe exactly how toothbrushes fall in a vacuum.

Problem #2: Theories are always doomed to remain theories. I haven't dropped my toothbrush in every possible location at every possible time to ensure that the theory accurately describes toothbrushes falling everywhere at every time. Therefore, my theory will forever remain a theory: I have pretty good confidence that this is how it works, but it's impossible to be sure. No matter how many ways I drop a toothbrush, I might be surprised one time to discover things don't go the way I expect. Sure enough I would. I would discover that at higher altitudes (in a vacuum), the toothbrush would fall slightly slower since I'm farther away from the center of mass of the Earch. If I dropped it from a great enough height, I'd see it gain mass and slow down as it approached the speed of light, according to relativity. If I dropped it from a great height not in a vacuum, I'd see it hit terminal velocity as the air particles bumping into it faster and faster offset the effects of gravity. This is fine too; I understand that a theory is a description of how I think things work from my experience, and I always might be wrong.

Category 2: Problems I Don't Understand

These problems I don't understand the implications of. Clearly they are not serious objections to science, since science has accomplished so much in spite of them. I don't know if they are fundamental issues with the underpinnings of science, or if I'm just confused and need to get straightened out.

Problem 3: At some point you have to jump from abstract to concrete, and I don't really understand the details of the jump.

When I think about a toothbrush falling, I'm working in the abstract math world. I'm assuming that actual physical "space" works exactly like mathematical 3-d space: there are infinite numbers of continuous points, and matter within that space exists within a closed surface with a certain density. That's a mathematical abstraction though that just kinda seems to work like reality, but they're only related by this foggy "I think it works a bit like that" feeling that I have no confidence in. So my description of how toothbrushes fall is really a set of rules for my toothbrush abstraction (my closed curve in math 3-d space with a density function within the surface). What do I really mean when I use that abstraction to describe the real world that actually has molecules and atoms and quarks, etc... etc... and is not an actual density function in math space? I don't know. I have kind of a foggy idea that you could make a set of rules that map your math model to predictions about what your measurement tools will read with various experiments. Kind of a real-world to math-model interface definition. I'm not really happy with my understanding of this yet though.

Problem 4: What the heck is this reality we're describing anyway? How do I know about toothbrushes in the first place? My rods and cones are stimulated to make a mental image of the toothbrush, and the sensors in my hands and mouth seem to tell me something is there. And I could taste it, smell it and hear it too. But that's all I've got! Who knows what it's like out there! Is there some kind of reality outside of my head? Seems to be that way; I think The Superhero exists and we seem to agree on what's out there. Does it make sense to talk about "out there"? All I know is what's in my head. Chris Langan addresses some of these issues in CTMU.

I think the way it works is that there's 2 separate problems: the mental to real-world (or math-model to real-world) mapping is one problem, and that's the one that's fuzzy for me. Then science sits on top of that and uses it, and has the problems in Category 1, which I've got under control.

That's all I've got for now; I'll report back when I figure it out!

There are some problems you encounter when you try to figure how stuff works in the real world. Some of them are very clear to me; they're problems, but I understand them. There are other problems that aren't very clear to me, and hang around in the back of my mind like little nagging doubts. Let me explain.

This morning I was brushing my teeth and imagined that I knew nothing about physics and was trying to figure out what happens when you drop a toothbrush. That's all science is after all: you see stuff happen and try to understand it better and explain it.

So what would I do?

I'd start dropping the toothbrush and watching it. I'd watch it again and again. Soon I'd probably notice that it starts out slow and speeds up as it falls. Maybe I'd get a video camera and videotape the toothbrush falling and watch the tape frame by frame, and figure out exactly how fast it's falling. I'd notice that it falls at almost the exact same way every time. Sooner or later I'd come up with the Theory of Falling Toothbrushes, which might be stated as follows:

Toothbrushes fall at a constant acceleration: 9.8m/s2

So, is this a good theory? It has some things in it's favour, principally that it predicts the position of the falling toothbrush at a given time to within the error tolerance of most experimental setups you might imagine.

This theory is as good as a scientific theory can be. It has some problems, but, as far as I can tell, these problems are fundamental to scientific theories; that is, these problems exist for every scientific theory that could be invented.

Here are the problems I can see with this:

Category 1: Problems I Understand

These problems are not particularly interesting. They're just occupational annoyances that scientists face. I'll explain them here to distinguish them from the interesting questions.

Problem #1: Almost every physical process you can observe is very very complicated. For instance, when you drop a toothbrush, it bangs into air molecules, and starts out with a small bit of angular momentum since you can't drop it straight down. These will make your experiment come out a bit different every time, and the the complications they introduce will be incalculable. This is not news: The Theory of Falling Toothbrushes actually describes what would happen if you dropped a toothbrush from a perfect dropping machine that imparts no "twist" or "push" as it drops, in a perfect vacuum. If this was the only objection to the theory, it would still describe exactly how toothbrushes fall in a vacuum.

Problem #2: Theories are always doomed to remain theories. I haven't dropped my toothbrush in every possible location at every possible time to ensure that the theory accurately describes toothbrushes falling everywhere at every time. Therefore, my theory will forever remain a theory: I have pretty good confidence that this is how it works, but it's impossible to be sure. No matter how many ways I drop a toothbrush, I might be surprised one time to discover things don't go the way I expect. Sure enough I would. I would discover that at higher altitudes (in a vacuum), the toothbrush would fall slightly slower since I'm farther away from the center of mass of the Earch. If I dropped it from a great enough height, I'd see it gain mass and slow down as it approached the speed of light, according to relativity. If I dropped it from a great height not in a vacuum, I'd see it hit terminal velocity as the air particles bumping into it faster and faster offset the effects of gravity. This is fine too; I understand that a theory is a description of how I think things work from my experience, and I always might be wrong.

Category 2: Problems I Don't Understand

These problems I don't understand the implications of. Clearly they are not serious objections to science, since science has accomplished so much in spite of them. I don't know if they are fundamental issues with the underpinnings of science, or if I'm just confused and need to get straightened out.

Problem 3: At some point you have to jump from abstract to concrete, and I don't really understand the details of the jump.

When I think about a toothbrush falling, I'm working in the abstract math world. I'm assuming that actual physical "space" works exactly like mathematical 3-d space: there are infinite numbers of continuous points, and matter within that space exists within a closed surface with a certain density. That's a mathematical abstraction though that just kinda seems to work like reality, but they're only related by this foggy "I think it works a bit like that" feeling that I have no confidence in. So my description of how toothbrushes fall is really a set of rules for my toothbrush abstraction (my closed curve in math 3-d space with a density function within the surface). What do I really mean when I use that abstraction to describe the real world that actually has molecules and atoms and quarks, etc... etc... and is not an actual density function in math space? I don't know. I have kind of a foggy idea that you could make a set of rules that map your math model to predictions about what your measurement tools will read with various experiments. Kind of a real-world to math-model interface definition. I'm not really happy with my understanding of this yet though.

Problem 4: What the heck is this reality we're describing anyway? How do I know about toothbrushes in the first place? My rods and cones are stimulated to make a mental image of the toothbrush, and the sensors in my hands and mouth seem to tell me something is there. And I could taste it, smell it and hear it too. But that's all I've got! Who knows what it's like out there! Is there some kind of reality outside of my head? Seems to be that way; I think The Superhero exists and we seem to agree on what's out there. Does it make sense to talk about "out there"? All I know is what's in my head. Chris Langan addresses some of these issues in CTMU.

I think the way it works is that there's 2 separate problems: the mental to real-world (or math-model to real-world) mapping is one problem, and that's the one that's fuzzy for me. Then science sits on top of that and uses it, and has the problems in Category 1, which I've got under control.

That's all I've got for now; I'll report back when I figure it out!

Thursday, February 19, 2009

The Crazy Curve

I have a theory about kids and the wacky stuff they say. When kids start to talk, they can't say much, so when something comes out, it's just one out of a few words they know. When you get to be a teenager, you can construct sentences to say anything you want, but you're smart enough by then to know which are the truly ridiculous things and keep them in. There's kind of a sweet spot in the middle, somewhere between 5 and 8, where kids think up all kinds of weird stuff, and they don't know it's ridiculous, and they can articulate it.

In my head, it looks like this:

My kids (ages 1/3/4/4) are just getting into the zone these days, especially the twins. When I watch them and The Superhero is off doing something else, I like to write down the funny things they say so she can read them later. Today I'll share them with the rest of you too.

My kids (ages 1/3/4/4) are just getting into the zone these days, especially the twins. When I watch them and The Superhero is off doing something else, I like to write down the funny things they say so she can read them later. Today I'll share them with the rest of you too.

This afternoon I was helping them with a video game and told Twin A how he had to move something. To which he started to sing:

Twin A: "I like to move it move it, I like to move it move it."

Number 3: "I like to MOVE it too!"

Just now I went upstairs and heard a ruckus going on in the 3 older kids' room so I went in to tell them to quiet down and go to sleep.

Me: "Everyone, I have two things to say: 1) That's a very nice pepperoni song you're singing, and 2) It's time for everyone to find a pillow and a bed."

Twin A: "The soup is all over me!"

Me: "Excuse me?"

Twin A: "The soup is all over me! I'm wet!"

Twin B: "This is our Jumping Bed!" (as he scurries off to the other bed which is presumably the Sleeping Bed).

Number 3: "Can I sleep in the bucket?" (They have a large Rubbermaid bucket in their room that they've emptied of toys).

Me: "Yes, you may sleep in the bucket." (Number 3 proceeds to put his pillow into the bucket and curl up in it).

They'd better start sliding down the other side of the crazy curve before they start looking for a woman to marry. Or date. Or even talk to. That is all I have to say.

In my head, it looks like this:

My kids (ages 1/3/4/4) are just getting into the zone these days, especially the twins. When I watch them and The Superhero is off doing something else, I like to write down the funny things they say so she can read them later. Today I'll share them with the rest of you too.

My kids (ages 1/3/4/4) are just getting into the zone these days, especially the twins. When I watch them and The Superhero is off doing something else, I like to write down the funny things they say so she can read them later. Today I'll share them with the rest of you too.This afternoon I was helping them with a video game and told Twin A how he had to move something. To which he started to sing:

Twin A: "I like to move it move it, I like to move it move it."

Number 3: "I like to MOVE it too!"

Just now I went upstairs and heard a ruckus going on in the 3 older kids' room so I went in to tell them to quiet down and go to sleep.

Me: "Everyone, I have two things to say: 1) That's a very nice pepperoni song you're singing, and 2) It's time for everyone to find a pillow and a bed."

Twin A: "The soup is all over me!"

Me: "Excuse me?"

Twin A: "The soup is all over me! I'm wet!"

Twin B: "This is our Jumping Bed!" (as he scurries off to the other bed which is presumably the Sleeping Bed).

Number 3: "Can I sleep in the bucket?" (They have a large Rubbermaid bucket in their room that they've emptied of toys).

Me: "Yes, you may sleep in the bucket." (Number 3 proceeds to put his pillow into the bucket and curl up in it).

They'd better start sliding down the other side of the crazy curve before they start looking for a woman to marry. Or date. Or even talk to. That is all I have to say.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

What Should I Do?

There are a few things that I learnt in school that have really stuck in my head - where I've been so excited to learn about them that they went straight into long term memory.

A lot of the stuff in Psychology 101 is like that for me. When I went to university I knew nothing about psychology, but I thought it would be the coolest thing to learn about. Imagine, finding out how people think, feel, remember, behave, and so on! I ended up taking the course twice, since The Superhero took it first, and I tagged along to the lectures, and then I took it myself later.

Anyhow, a whole bunch of the stuff we learnt in that class stayed with me, and one of them is the hierarchy of needs. The idea is that there are different levels of needs, from very basic (shelter, food) to more sophisticated (sense of belonging, purpose), and you don't care about the upper levels until you've satisfied the lower ones.

There's something to this theory: if you ever hear people talking about times when they didn't have enough to eat, all they can talk about is wanting food. They don't care about anything else. Same thing whenever you go through a major life transition; you don't really care about anything else until your life is back in order.

I find myself recently with the weird difficulty of struggling with the needs at the top of the pyramid. I can recall the second-to-last semester of university in which we had baby twins to care for and The Superhero and I were both in school full time; we were totally focused on the everyday demands of life and getting through the term without failing a course of losing a baby. But now, as we ease out of the super-hard work section of our life, I feel a weird kind of emptiness that comes from getting exactly what you asked for.

The Superhero and I basically have it figured out. The bills get paid. We're healthy. Our family is happy. We have friends. We have hobbies. We have no "real problems". In fact it's typical for The Superhero or I to catch the other complaining about something relatively unimportant and say "Please talk to me when you have a Real Problem.".

So I find myself with this funny kind of life-optimization problem. I think to myself "Ok, so now what?". I'm 27 now. I'm going to die when I'm 80 or so. That's a lot of time in the middle! Today I have extra time and energy over and above what I need to keep the basics of life flowing smoothly. As time goes on, I'll have only more... the kids will get more independent and eventually leave, The Superhero and I will have more spare money, etc.

So what should I do? What will my future 80-year old self wish I had done? I have a bunch of disconnected thoughts on this, but most of it is probably wrong, and I don't know anything about how it fits together. Nonetheless, here are my thoughts on how to improve my life, in no particular order:

A lot of the stuff in Psychology 101 is like that for me. When I went to university I knew nothing about psychology, but I thought it would be the coolest thing to learn about. Imagine, finding out how people think, feel, remember, behave, and so on! I ended up taking the course twice, since The Superhero took it first, and I tagged along to the lectures, and then I took it myself later.

Anyhow, a whole bunch of the stuff we learnt in that class stayed with me, and one of them is the hierarchy of needs. The idea is that there are different levels of needs, from very basic (shelter, food) to more sophisticated (sense of belonging, purpose), and you don't care about the upper levels until you've satisfied the lower ones.

There's something to this theory: if you ever hear people talking about times when they didn't have enough to eat, all they can talk about is wanting food. They don't care about anything else. Same thing whenever you go through a major life transition; you don't really care about anything else until your life is back in order.

I find myself recently with the weird difficulty of struggling with the needs at the top of the pyramid. I can recall the second-to-last semester of university in which we had baby twins to care for and The Superhero and I were both in school full time; we were totally focused on the everyday demands of life and getting through the term without failing a course of losing a baby. But now, as we ease out of the super-hard work section of our life, I feel a weird kind of emptiness that comes from getting exactly what you asked for.

The Superhero and I basically have it figured out. The bills get paid. We're healthy. Our family is happy. We have friends. We have hobbies. We have no "real problems". In fact it's typical for The Superhero or I to catch the other complaining about something relatively unimportant and say "Please talk to me when you have a Real Problem.".

So I find myself with this funny kind of life-optimization problem. I think to myself "Ok, so now what?". I'm 27 now. I'm going to die when I'm 80 or so. That's a lot of time in the middle! Today I have extra time and energy over and above what I need to keep the basics of life flowing smoothly. As time goes on, I'll have only more... the kids will get more independent and eventually leave, The Superhero and I will have more spare money, etc.

So what should I do? What will my future 80-year old self wish I had done? I have a bunch of disconnected thoughts on this, but most of it is probably wrong, and I don't know anything about how it fits together. Nonetheless, here are my thoughts on how to improve my life, in no particular order:

- The key to happiness seems to be improvement. It doesn't matter where you are, happiness seems to be all about how quickly things are getting better. I don't know what this means in terms of a plan, but there you have it.

- It makes me really happy to start to learn about something new, or start learning a new skill or hobby. So I think I should do that a lot.

- As the kids get older, I can teach them everything. I've learnt most of the easy stuff, but they don't even know how to add yet! So I can teach them stuff, both academic and life-skill-wise.

- I think I'm missing out on a bunch of life by not being open to people. Meeting people exposes you a whole lot of randomness and different points of view that you wouldn't otherwise think of. For instance I'm reading a book called Classic Feynman, which is a collection of talks that Richard Feynman gave, and I've learnt from him to translate complicated things into things that I understand very clearly before thinking further.

- I think I should learn about everything. The library is full of books about everything you could ever think of! I believe there's a limitless source of books I'd be really excited to read, so there's no excuse for being bored when there's a public library where I'm living.

- One of my favourite things to do is have fun with The Superhero. So I'll always do a lot of that too.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

Me and My Time

Disclaimer: This post will only be of interest for the truly dorky-at-heart. I will accept no liability for any wasted time or annoyance this may cause. You will not get this time back.

I have some good news and some bad news: I am continuing to get to work on time, but that in no way guarantees that I get anything more useful done than if I had stayed in bed.

I'm working on a project now that I have to get done roughly for the end of the month. I find some days that I end up doing everything else at work and not the main project I'm supposed to be doing, and other days I get lots done on the project. Until a few days ago, I had a bunch of nagging questions that I had no way to answer, like:

Throughout the day, every time I switch tasks, I enter what I did and how long I did it for. I also enter how much I now estimate I have left on that task before it's done. For example, if I have a 4-hour task, and I work on it for 2 hours, hopefully I think there's 2 hours left. But maybe I ran into a snag and now I think there's 3 hours left still, so although I put in 2 hours, I only got 1 hour's worth of "estimated" work done.

The output of spreadsheet is, among a couple of other things, 3 numbers.

The results? Dismal. Problem number one is that I spend hardly any time on the stuff I should be doing. Focus efficiency has been less than 50%. Work efficiency has been ok; I've been spending about 80%-90% of my time in the office actually doing something useful. When I actually sit my butt down and work on what I should be working on, I'm getting it done faster than expected. My estimation efficiency is more than 100%.

To get this project done, I need to clear 5 estimated hours per day for the rest of the month. I've barely done this over the last two days, and I wasn't coming close before I started measuring.

So there you have it: this is how I spend my productive hours, working like a computer, at a computer, programming computers.

I have some good news and some bad news: I am continuing to get to work on time, but that in no way guarantees that I get anything more useful done than if I had stayed in bed.

I'm working on a project now that I have to get done roughly for the end of the month. I find some days that I end up doing everything else at work and not the main project I'm supposed to be doing, and other days I get lots done on the project. Until a few days ago, I had a bunch of nagging questions that I had no way to answer, like:

- How many more hours of work do I have left?

- Can I finish my project on time?

- Am I spending enough time on my main work in comparison to other tasks that come up?

- Am I actually getting anything useful done at work?

Throughout the day, every time I switch tasks, I enter what I did and how long I did it for. I also enter how much I now estimate I have left on that task before it's done. For example, if I have a 4-hour task, and I work on it for 2 hours, hopefully I think there's 2 hours left. But maybe I ran into a snag and now I think there's 3 hours left still, so although I put in 2 hours, I only got 1 hour's worth of "estimated" work done.

The output of spreadsheet is, among a couple of other things, 3 numbers.

- Work efficiency: This is the time I spend doing productive things divided by the total number of hours in the office.

- Focus efficiency: This is the time I spend working on the stuff I'm "supposed" to be working on compared to random things that come up (e-mail, meetings, etc.).

- Estimation efficiency: This is the estimated hours I've gotten through (that is, what I estimate remains for all my tasks at the beginning of the day, minus the same thing at the end of the day), divided by the actual hours I put in on those tasks.

The results? Dismal. Problem number one is that I spend hardly any time on the stuff I should be doing. Focus efficiency has been less than 50%. Work efficiency has been ok; I've been spending about 80%-90% of my time in the office actually doing something useful. When I actually sit my butt down and work on what I should be working on, I'm getting it done faster than expected. My estimation efficiency is more than 100%.

To get this project done, I need to clear 5 estimated hours per day for the rest of the month. I've barely done this over the last two days, and I wasn't coming close before I started measuring.

So there you have it: this is how I spend my productive hours, working like a computer, at a computer, programming computers.

Monday, February 9, 2009

Human Spectrophotometry

The Superhero and I have a running metaphor called human spectrophotometry.

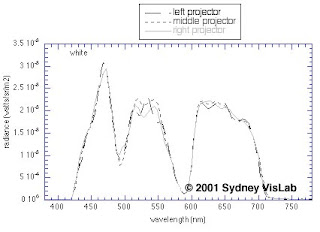

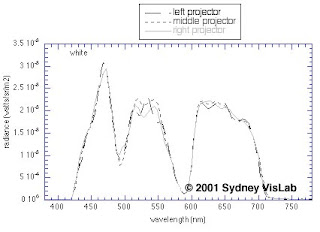

Spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometry

is a way of determining the constituent substances in a solution. The idea is to send varying frequencies of light through a solution and see which frequencies are absorbed and which pass through. Every constituent substance has a "signature" of light it absorbs, and if, for instance, you see 3 spikes in the spectrophotometry graph (see left), you can say that you have 3 different chemicals mixed together, and you can tell what they are from where the spikes show up.

The idea of "human" spectrophotometry is that people have a variety of different constituent properties and you could plot a graph describing what any given person is like. For instance, I have a very spiky spectrophotometry: I have areas in which I'm very strong (logical thinking, for instance) and areas in which I'm very weak (dealing with people). The Superhero's spectrophotometry is very even and very high: she's well-rounded and talented across the board.

The Twins are just like me; they're spectrophotometry is also very spiky, and spiky in the same spots. While I'm sure they'll have lifelong difficulties making friends and decoding women, they're great when it comes to learning letters, numbers, days of the week, and the like. I still recall the day when they demonstrated that they could count to 10 in Spanish, sans parental instruction. Their parents may have been taking refuge with Dora theBabysitter Explorer around that time. Hard to say.

In any case, up until this past weekend, the Twins have had a weird blind spot for understanding the differences between the different meals. Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner were interchangeable synonyms until I decided to make this:

Ever since, we've been crystal clear. We have to read through all the characteristics of the various meals every time we sit down to eat. Is it morning, afternoon or night? How many meals have we had today?

There are some very nice changes as the kids are getting older. They don't scream in the night, and I get to teach them stuff! I love to explain stuff to people! Even if they won't need math help as much as I'd like, there are all kinds of holes in what the school system teaches. Like how to have a nice marriage, or how to make a budget, or how to delegate, or the importance of exercise. One day, we can even sit down and draw our very own spectrophomometry graphs!

Spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometryis a way of determining the constituent substances in a solution. The idea is to send varying frequencies of light through a solution and see which frequencies are absorbed and which pass through. Every constituent substance has a "signature" of light it absorbs, and if, for instance, you see 3 spikes in the spectrophotometry graph (see left), you can say that you have 3 different chemicals mixed together, and you can tell what they are from where the spikes show up.

The idea of "human" spectrophotometry is that people have a variety of different constituent properties and you could plot a graph describing what any given person is like. For instance, I have a very spiky spectrophotometry: I have areas in which I'm very strong (logical thinking, for instance) and areas in which I'm very weak (dealing with people). The Superhero's spectrophotometry is very even and very high: she's well-rounded and talented across the board.

The Twins are just like me; they're spectrophotometry is also very spiky, and spiky in the same spots. While I'm sure they'll have lifelong difficulties making friends and decoding women, they're great when it comes to learning letters, numbers, days of the week, and the like. I still recall the day when they demonstrated that they could count to 10 in Spanish, sans parental instruction. Their parents may have been taking refuge with Dora the

In any case, up until this past weekend, the Twins have had a weird blind spot for understanding the differences between the different meals. Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner were interchangeable synonyms until I decided to make this:

Ever since, we've been crystal clear. We have to read through all the characteristics of the various meals every time we sit down to eat. Is it morning, afternoon or night? How many meals have we had today?

There are some very nice changes as the kids are getting older. They don't scream in the night, and I get to teach them stuff! I love to explain stuff to people! Even if they won't need math help as much as I'd like, there are all kinds of holes in what the school system teaches. Like how to have a nice marriage, or how to make a budget, or how to delegate, or the importance of exercise. One day, we can even sit down and draw our very own spectrophomometry graphs!

Thursday, February 5, 2009

Habits and the Clear Path to Success

I have a crazy weekday schedule. I get to work around 6:30 in the morning and leave around 3:30.

A few weeks back, I was getting to work at more like 6:40-6:50. The main problem was that I was getting lazy at night and leaving stuff to do in the morning, and also procrastinating leaving in the morning, since running 6 1/2 km in double-digit sub-zero temperatures takes more energy than I tend to have at 5:30 in the morning.

Anyhow, missing 10-20 minutes of work is not the end of the world, but it bothered, me, mainly because I wasn't able to take control of it.

This is the kind of problem in which my father-in-law would say there is a "clear path to success". There's all kinds of problems which are actually complicated and require complicated solutions, but there are a whole class of problems in which the solution is painfully obvious, and yet oddly elusive. I know exactly how to solve this problem. Get my shit together the night before. Leave promptly in the morning. Don't be a lazy ass. And yet I didn't do it; day after day I was showing up late.

I have some opinions about this. I'm sure I'm wrong (here's why), but nonetheless it's a working theory:

It took me a couple of days to figure out what to do, but the moment I thought of the New Plan, I knew it would be successful. And it has been; my work start time now varies a bit, but the average start time is 6:30. Exactly 6:30.

My scheme is this:

Day 1: Get up whenever the hell I want. Try to get to work on time.

Day 2: Adjust my alarm by whatever would have been needed to get to work on time. E.g. if I set the alarm for 5:30 on day one and got to work 20 minutes late, set it for 5:10 the next day.

Day 3 (and so on): repeat Day 2.

Now, if I'm slow one day, I pay for it the next day. Getting to work on time was never good enough motivation to hustle in the morning, but getting to sleep more the next night sure is!

On that note, I'm off to bed... wake-up time is 5:04 tomorrow!

A few weeks back, I was getting to work at more like 6:40-6:50. The main problem was that I was getting lazy at night and leaving stuff to do in the morning, and also procrastinating leaving in the morning, since running 6 1/2 km in double-digit sub-zero temperatures takes more energy than I tend to have at 5:30 in the morning.

Anyhow, missing 10-20 minutes of work is not the end of the world, but it bothered, me, mainly because I wasn't able to take control of it.

This is the kind of problem in which my father-in-law would say there is a "clear path to success". There's all kinds of problems which are actually complicated and require complicated solutions, but there are a whole class of problems in which the solution is painfully obvious, and yet oddly elusive. I know exactly how to solve this problem. Get my shit together the night before. Leave promptly in the morning. Don't be a lazy ass. And yet I didn't do it; day after day I was showing up late.

I have some opinions about this. I'm sure I'm wrong (here's why), but nonetheless it's a working theory:

- There are some "clear path to success" problems that some people will never have. I will never have problems with overspending and debt. I hate debt and I rarely have the impulse to buy anything. I don't try hard to stay out of debt, it's just who I am. It's not a matter of will power or zen, I just don't want to buy stuff. The Superhero really loves to run. She'll never be out of shape because she really likes to exercise. It's just who she is.

- Everyone has some "clear path to success" problems that they struggle with. Punctuality is one of mine. My instinct to leave for scheduled events is not strong enough to get me there on time.

- "Will power" is an unreliable way to solve these problems. The best way I've found is to get creative and find a strategy other than will power to make myself behave properly. For instance, in my early days of running, I ran with my brother-in-law, which forced me to get up in the morning. Now running is my transportation to work, which is often my only way to get there.

- Sometimes the only way fix the issue is suck it up and change my habits. This is trickier than it sounds! I've read that it takes about 3 months to make new habit. The "new kick" motivation wears off after a week or 2. That's a long 2.5 month gap in there to stick with a new behaviour before the "habit pain" of doing something out of the ordinary wears off.

It took me a couple of days to figure out what to do, but the moment I thought of the New Plan, I knew it would be successful. And it has been; my work start time now varies a bit, but the average start time is 6:30. Exactly 6:30.

My scheme is this:

Day 1: Get up whenever the hell I want. Try to get to work on time.

Day 2: Adjust my alarm by whatever would have been needed to get to work on time. E.g. if I set the alarm for 5:30 on day one and got to work 20 minutes late, set it for 5:10 the next day.

Day 3 (and so on): repeat Day 2.

Now, if I'm slow one day, I pay for it the next day. Getting to work on time was never good enough motivation to hustle in the morning, but getting to sleep more the next night sure is!

On that note, I'm off to bed... wake-up time is 5:04 tomorrow!

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

Thank You For Screaming, Part II

I have some bad news for you today. I'm very sorry to be the one who has to break the news to you, but here it is: You're wrong about most things.

Oh, I know, there's a big category of stuff you're not wrong about. Like what city you live in. And where the grocery stores are near your house. And what your kids' name are. You've got that stuff under control.

But there's a whole collection of stuff in which you don't know your ass from your elbow. Like political views, religious views, moral views, opinions on how to parent, teach, be a good friend, and manage your life. I'm really very sorry, but you just don't know nearly as much as you think you do on these topics. I don't either.

I've learnt something over the last couple of years, mainly from studying chess and in my job programming computers, and that is the importance of testing. When you're trying to figure out how something will work, most things are just really, really complicated. You're not going to figure them out just by thinking; you're only going to figure them out by testing.

I slowly became convinced of this as I went through software project after software project and observed two things:

I became quite impressed with the intrinsic complexity of these types of problems, and how invariably the failures of the project planning or the chess position-solving could only be uncovered by watching the systems fail and observing where the problems were, and never by just "thinking it through".

Intrigued, I observed everyday life and observed the same types of things:

But questions of the philosophical sort are typically untestable, and I'm convinced we're generally wrong about the things we tend to believe. For instance:

Anyhow, all this comes to one final example; something that gets tested everyday, and has totally the opposite answer to what you'd expect.

When The Superhero gets mad and yells at me, how does it affect the interaction? Our day? Our marriage?

Totally for the better, on all counts. Who would have thought? Not me.

It diffuses the fight; beforehand it's resentment in The Superhero's head. The yelling lets it out. And it makes me laugh. I have no explanation for this. It's complicated! That's why you must test stuff! The laughter diffused the situation. The Superhero feels loved, relaxed, and much better off than before.

The unexpected laughter is not short-lived. If I was grumpy before, it cheers me up. My day gets brigher. Totally unexpected. But true.

Furthermore, it has a wonderful effect on our marriage. I never have to worry that I'm walking on The Superhero and she isn't telling me. I know if she's upset she'll let me know and stand up for herself. No long-term resentment.

Overall the yelling is a great thing, and nobody would have guessed.

This, in addition to the unexpected benefits of Twin B's shrieking? Mind-boggling, but true.

Where would I be if I didn't have such a charming family full of people to yell at me?

Oh, I know, there's a big category of stuff you're not wrong about. Like what city you live in. And where the grocery stores are near your house. And what your kids' name are. You've got that stuff under control.

But there's a whole collection of stuff in which you don't know your ass from your elbow. Like political views, religious views, moral views, opinions on how to parent, teach, be a good friend, and manage your life. I'm really very sorry, but you just don't know nearly as much as you think you do on these topics. I don't either.

I've learnt something over the last couple of years, mainly from studying chess and in my job programming computers, and that is the importance of testing. When you're trying to figure out how something will work, most things are just really, really complicated. You're not going to figure them out just by thinking; you're only going to figure them out by testing.

I slowly became convinced of this as I went through software project after software project and observed two things:

- The project always takes way more time than you estimate.

- The problems that arise during the project are never the ones you predict.